[ad_1]

Ofsted and the Care Quality Commission (CQC) have been inspecting local area SEND services since 2016. At the start of 2023, they introduced a new framework that changed the way they inspect education, health and social care SEND services.

One year on, how are these inspections panning out?

Out with the Old, In With The New

The first set of Ofsted and CQC local area SEND inspections ran as a one-off, from 2016 to 2022. They checked how well local authorities and NHS clinical commissioning groups were implementing the SEND reforms introduced under the 2014 Children and Families Act.

After a few years, it became clear that this wasn’t going to be enough. So Ofsted and CQC were tasked by the Department for Education (DfE) to come up with a new inspection approach. In response, they designed a continuous cycle of inspections, focusing more on the lived experiences and outcomes of children and young people with SEND.

The first inspections under this new framework – rebadged as ‘Area SEND’ Inspections – began in January 2023. They’re different in structure and approach from the first round. You can find a list of the differences in this post.

The area SEND inspections look at the ‘local area partnership’. That’s the local authority’s SEND education services, the services provided by the NHS Integrated Care Boards (ICBs) that operate within the LA’s geographic area, and also aspects of LA social care. The new framework also looks at alternative provision.

A recap of new outcomes types

The range of inspection outcomes has also changed. Under the old system, inspection outcomes were binary. Inspectors either identified significant weaknesses in local area SEND services, which then prompted a structured improvement plan and a re-visit – or they didn’t find any, in which case the process finished.

Under the new ‘Area SEND’ Framework, there are three possible inspection outcomes, each couched in a slightly ungainly way.

The best possible outcome for the local area partnership, which we’ll shorten to ‘positive,’ is this:

“The local area partnership’s SEND arrangements typically lead to positive experiences and outcomes for children and young people with SEND. The local area partnership is taking action where improvements are needed.”

Local area partnerships rated as ‘positive’ will be inspected again in around five years. Put bluntly, a local area partnership can get this outcome without being expected to deliver anything like an outstanding quality of SEND service. But even for areas rated ‘positive,’ the inspectors identify areas for improvement, and expect local area partnerships to do something about it.

The middle-ranking outcome in the new inspection framework, which we’ll call ‘inconsistent’, runs like this:

“The local area partnership’s arrangements lead to inconsistent experiences and outcomes for children and young people with SEND. The local area partnership must work jointly to make improvements.”

If this is the outcome, then the local area’s next full inspection will be brought forward – usually to within three years, rather than five– but there won’t be an interim monitoring inspection.

The lowest possible outcome – which we’ll shorten to ‘significant concerns’ – is this:

“There are widespread and/or systemic failings leading to significant concerns about the experiences and outcomes of children and young people with SEND, which the local area partnership must address urgently.”

This happens when inspectors have identified “significant concerns about the experiences and outcomes of children and young people, because of particular systemic or widespread failings that have a significant negative impact on the experiences and outcomes of children and young people.”

There’s no formal definition of how bad things have to be considered a ‘priority action’, it’s mostly a matter of inspector judgement. If a local area gets this outcome, then they have to produce a plan showing how they are going to improve things. Before, this was known as a ‘written statement of action.’ Now, it’s got another, clunkier name: a “Priority Action Plan (Area SEND).”

If an area gets this outcome, then it will be subjected to a monitoring inspection, 18 months on. This will concentrate on the areas for priority action identified in the previous full inspection, but doesn’t have to be confined to those.

Area SEND Inspection Outcomes in 2023

It’s impractical to compare inspection outcomes across the old and new systems. So it’s unwise to use the new inspection outcome reports to make sweeping judgements about whether things are getting better or worse over time, either nationally or at local level. But for context, most local areas had significant weaknesses identified in their SEND services under the old system.

How has the first year done? It depends how you look at it…

So how have local area partnerships fared in the first year of the new framework?

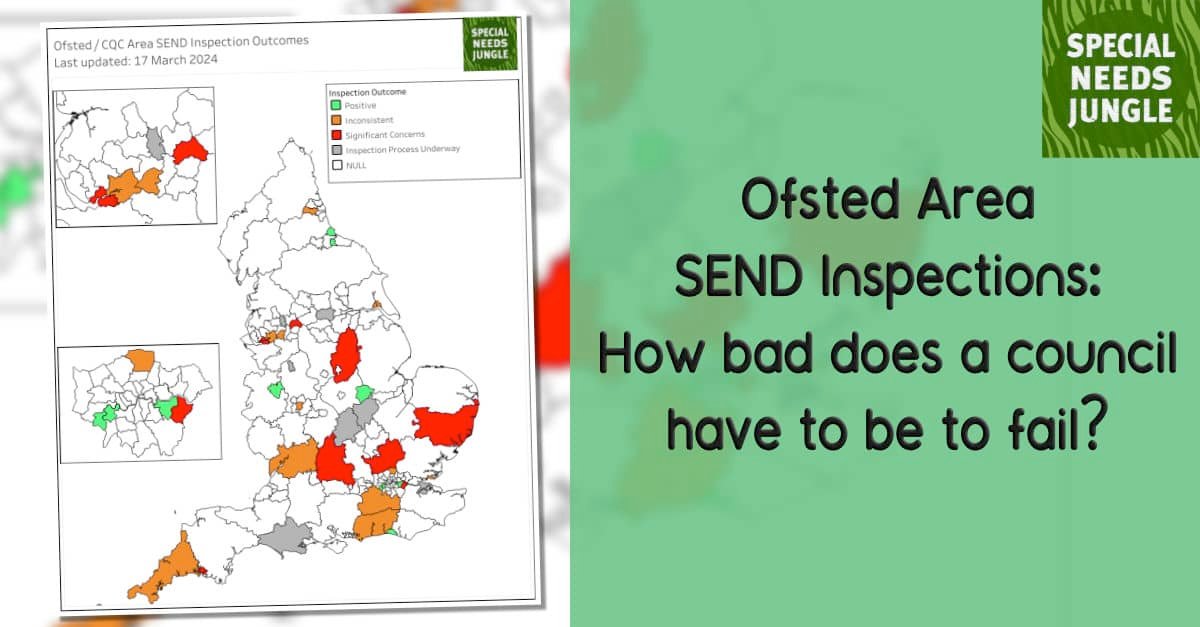

We counted 26 area SEND inspections that took place in 2023 under the new framework. Inspection outcomes have been fairly evenly distributed across the three outcome categories.

- 7 local area partnerships were given a ‘positive’ outcome by inspectors;

- 11 local area partnerships were described as ‘inconsistent’; and

- Inspectors found ‘significant concerns’ in 8 local area partnerships.

There are 153 local area SEND partnerships. Ofsted and CQC have reported on only 26 of them so far. This is the first year of what will be a five-year inspection cycle. So any conclusions here are pretty tentative.

😀 If you’re feeling optimistic, then you can use this evidence to show that three out of every ten local area partnerships are doing a good job for most of their children and young people with SEND.

🙁 If you’re feeling pessimistic, it looks like three-quarters of local area partnerships have problems with their SEND services that are bad enough to warrant accelerated inspections, with three out of every ten local area partnerships having problems bad enough to warrant priority action.

What positive things have inspectors found?

In the seven local area partnerships that got a ‘positive’ inspection outcome, there are a few things that popped up regularly.

- Local area partnerships tended to do well where inspectors saw persuasive evidence of leaders working well with families of children and young people with SEND.

- Likewise, where inspectors saw evidence of education, health and social care leaders working together constructively and coherently, with a clear strategic ambition, they noted it approvingly.

- In the best-performing local areas under the new framework, early identification of need and rapid access to specialist support when needed scored well.

- Areas that know their own strengths and weaknesses, and can show what they’re doing about the weaknesses, also tend to do better.

What have inspectors found that requires improvement?

The things that worry area SEND inspectors most often haven’t changed a great deal from the 2016-2022 inspection cycle.

- Defective strategy and leadership are the most frequent things that trigger significant concerns, followed by

- problems with joint commissioning between education and health bodies.

- Inspectors have also registered significant concerns about service-specific weaknesses:

- things like long waiting lists for children with multiple needs,

- social care support for disabled children,

- problems with speech and language therapy,

- occupational therapy, and

- neurodevelopmental services.

Ofsted & CQC inspectors have also recommended improvements in other areas too. The most commonly identified areas involve problems with local areas’ Education, Health and Care Plan processes:

- slow production of EHCPs,

- backlogs of EHC needs assessments,

- incomplete collection of specialist advice,

- missing annual reviews, and others.

Other areas that are frequently identified for improvement include:

- problems with preparing children and young people with SEND for adulthood,

- problems with transitions between phases of education, and

- quality and sufficiency of alternative provision.

What have parents reported to us about the new area SEND inspections?

The feedback that we’ve received from parent carers has been mixed.

According to the inspection handbook, inspectors have to meet with parent carers at the start of the process. That’s a good thing, in principle: it gives inspectors a better chance to consider parental evidence while they’re thinking about what lines of inquiry to follow.

These meetings are supposed to include “representatives from the Parent Carer Forum and/or other representative groups of parents and carers.” Inspectors also collect evidence from parents via a survey, and by talking directly with a small number of parents in case study tracking meetings.

Several parents and parent groups have told us that this process has not always been smooth – particularly for parents who sit outside of the Parent Carer Forum system. Some of these groups have reported they’ve had to overcome initial resistance from inspectors to take their evidence.

Some parent groups have told us they’ve been very surprised at how low the bar seems to be for acceptable practice. One group assembled a detailed pack of evidence showing severe and enduring weaknesses in their local area partnership’s support for autistic children and young people. They shared this report with inspectors, but it appeared to cut little ice with them.

Others have noted inspectors often seem to be extremely relaxed about consistently appalling LA outcomes at the SEND First Tier Tribunal and the Local Government and Social Care Ombudsman.

Parents have also raised concerns with us about the depth of failure necessary for inspectors to register a significant concern with an area’s SEND service. Exceptionally bad – and occasionally lethal – failings in service do not necessarily trigger significant concerns. That’s fist-chewingly consistent with the new inspection framework, which says the threshold has to be “widespread and/or systemic failings.”

What’s acceptable?

This raises an important question: What level of SEND service do inspectors consider to be acceptable (or unacceptable) under the new area SEND inspection framework?

The framework and handbook shows a lot depends on inspector judgement, but they state clearly that Ofsted and CQC inspectors will not be looking in forensic detail at whether a local area partnership is complying with the law:

“The area SEND framework focuses on the impact of the local area partnership’s arrangements for children and young people with SEND. Its fulfilment of legal duties is part of this impact. Inspectors will not check compliance with every legal duty in relation to children and young people with SEND. However, there are legal duties underpinning our evaluation criteria. Where inspectors find that those duties are not being met, they will report on how this affects children and young people with SEND.”

The last sentence is illuminating. Inspectors do not automatically call out unlawful practice, but if they find that local area partnerships fall short of their statutory duties, they will usually describe what difference this has made.

How familiar are inspectors with SEND law? Ummm…

However, there are occasional examples where inspectors either do not appear to understand SEND law and regulations, or are willing to tolerate eye-wateringly unlawful practice.

For example, this excerpt from Gloucestershire’s recent inspection outcome letter:

“…there is overwhelming evidence of schools leading the annual review and EHC plan process without input from partnership services, developing their own systems to monitor changes to plans in the absence of revised plans. Although this is permitted within the SEND code of practice, it does not enable a multi-agency approach to reviewing the changing needs of children and young people.”

This ISN’T, in fact, permitted by the SEND Code of Practice, the SEND Regulations, or the Children and Families Act. Local authorities must review plans annually and amend them where required, and the person arranging an annual review meeting must obtain advice and information from a range of agencies.

Later, in the same report:

“currently parents and providers say the partnership does not accept information collated from private practitioners to better support children and young people through assessment and review processes in swiftly identifying need and securing support.”

As a blanket policy, this approach would NOT be consistent with the SEND Regulations. It wouldn’t survive 30 seconds’ contact with an average SEND Tribunal panel.

Also read: Announcing two new Directors for Special Needs Jungle!*

Too many missed legal deadlines? One is too many!

Another eyebrow-raising finding, this time from West Sussex’s recent inspection:

“Too many education, health and care needs assessments are not completed within the statutory timescales.”

The West Sussex local area partnership scored an ‘inconsistent’ rating in their report. The inspectors rightly listed EHCP timeliness as an area of improvement for the partnership. So what did ‘too many’ mean here? How many EHCPs produced out of statutory timescales were ‘too many’ to be fully acceptable, but not ‘too many’ to register significant concerns?

West Sussex’s own data provides an answer. In 2023, the LA finalised just 3% of their new EHCPs within the 20-week statutory timeframe. At the time of inspection in late 2023, it was taking West Sussex an average of 49 weeks to finalise new EHCPs— more than double the legal deadline.

This affected support for over 850 children and young people with SEND – but inspectors did not consider it a widespread or systemic failing, leading to a significant concern. It would be interesting to know why.

How poor do lived experiences need to be to be unacceptable?

Here’s an example from another recent report:

“Inspectors found systems that are too reactive, and, in some cases, this results in children, young people and families reaching crisis point before their needs are met. For example, we heard young people waiting too long for mental health assessments or not meeting the criteria for an assessment, even where health practitioners have supported their application. For some, hospital admission was the trigger for support.”

This local area partnership was judged to have inconsistent services, with no significant concerns identified.

Remember, these new area SEND inspections are supposed to look hard at the lived experiences of children and young people and their outcomes. Inspectors found evidence some children and young people in this local area could only obtain mental health support after being hospitalised. And yet, somehow, this doesn’t count as a significant concern.

The SEND system is clearly in crisis, sometimes for reasons that go well beyond the capacity and capability of local area partnerships to resolve. But there’s a danger here that crisis conditions become normalised, with inspections potentially ending up treating endemic bad practice as something that needs slow improvement, rather than urgent priority action.

This new area SEND inspection framework is still finding its feet, and quality is likely to improve. The first inspections in 2016 were sometimes astonishingly complacent, but they got better as time went on. Let’s hope the same trend happens with the new inspections, and the sooner the better for the sake of our disabled children and young people.

Also read:

Don’t miss a thing!

Don’t miss any posts from SNJ – simply add your email address below. You must click the link in the confirmation email you’ll receive to activate your free subscription.

You can also keep up with us by following our WhatsApp Channel!

Want more? Be an SNJ Patron!

SNJ is a non-profit company and everyone who writes here does so voluntarily. We need your support to help us with costs by donating once or as a regular patron. Regular donors get an exclusive SEND update newsletter as thanks! Find out more here

Related

[ad_2]

Source link

Leave a Reply